a sigh in a cavernous tunnel with no exit, is a piercing scream when it returns

a little tough to write this one but I attempt to think through curative violence (in tandem with normative violence), ableism and words of hope that cuts like a knife.

Isi hatiku: What is normative and curative violence?

[Disclamer: This example is not an attack on the campaign, school or creators of this video. It is to illustrate the inherent problems of visual culture and media representation of disability.]

Few months ago I came across a campaign video shot from the POV of a child with disability. The campaign was targeted to raise funds for families who may not afford the school fees.

You can view the video here: https://www.instagram.com/tv/CcWvtbkhBYY/?hl=en

I wrote down scenes from the last seven minutes of the video:

Prior to the dream sequence. (Seen from the POV of child)

Two parents seated on a sofa. Father is crying. Mother is comforting him. Mother wants to put child through school but they are struggling financially. Child is watching the scene unfold from his room.

Mother: You have done your best for this family but if Jamal is unable to be independent, what will happen if we are no longer around?

Father: Please forgive me, if I don’t help you around enough at home.

Mother: There is nothing for me to forgive. Jamal is our Amanah from Allah. We are fated to live this way.

Child’s Monologue:

The frown on their faces, tears in their eyes. Yes I am the cause of it.

I am a pearl in your hands, but (inaudible) is taking care of (inaudible).

[HIgh pitch ringing, increased heartbeat and shaky movements to indicate that child is having a seizure. Parents come running towards him. Both parents comfort him)

I bring on so much worries to the both of you, but you are resilient

[High pitch ringing stops and everything stabilises)

Father exclaming: Oh thank God, please don’t be afraid my love.

Monologue continues:

Oh Father and Mother, your semangat is extraordinary

To go through this life with me

[Mother starts to read prayer verses]

[Dream sequence begins with flowers and tree shots]

[Father and Mother appears]

Monologue continues:

In my dream, we are perfect.

But even if the reality is bitter

You sincerely accept me as I am

[Both father and mother are looking joyous and playing hide and seek with child. Beckoning him to come)

Father: I love you Jamal

Mother: Jamal, come here. Come here my love, come here.

Dream sequence ends

Parents applies to school and learns, from the teacher of financial help that they may receiving

Parents are relieved.

Mother: I hope that Jamal learns to be independent

Teacher: Yes we will help Jamal and all the children that are here the best that we can.

The parents applies to the school and are told that their application will be reviewed and they will be informed if they secure a slot.

Child: Is our dream coming true?

Mother receives a call and is informed that the application is successful. Mother and Child celebrates.

Scenes of classroom, literacy, numeracy, educators teaching children (including child). A scene of child folding clothes). Both scenes in child’s POV.

Monologue continues:

Your encouragement fuels my semangat,

Your semangat is my strength

For you, I will reach for the stars

The world will still judged but all of this is not important for me

POV breaks and you see child sitting in his wheelchair at the end of a corridor. He is clapping and smiling. His classmates are walking down the corridor. He lowers both his feet to the floor.

Child: As long as you believe that I can.

Both parents bear witness, brimming with hope. Mother has her hands clasps to her chest.

Child: Thats all I need

Child stands up smiling

Father and Mother is moved and looks at a teacher with gratitude. Mother touches teacher gently on the shoulder, nodding slightly.

Child stands holding the wall of the corridor, smiles to the camera and waves.

Ends with text on white background “Your sincerity can change everything”

Video directs viewer on where to make donations.

Video ends.

So what’s the problem here? It is such a moving video for such a wonderful cause. Don’t stir shit ila. Yeah well, most normative folks will fail to see the optics that are deep in ableism.

What is ableism?

This is the cut-paste definition:

“Ableism perpetuates a negative view of disability. It frames being nondisabled as the ideal and disability as a flaw or abnormality. It is a form of systemic oppression that affects people who identify as disabled, as well as anyone who others perceive to be disabled. Ableism can also indirectly affect caregivers”

Ableism comes in many forms (more on that later) but is due to the conditioning of society that the abled-body (body here means the whole range of intellectual, physical, and emotional capacities) is the superior body because it is the normative body. Thus anything that does not fall into this notion of the normative body is considered inferior.

The focus is then placed on the disabled body as being inadequate and unsuited to this normative society. So in other words, it’s all pretty fucked up in a deep and blinding manner that goes way, way back. For a disabled body to have full agency in society they need to be able to be (at the very least), normative passing or what we all know today as high functioning. And this is where normative and curative violence comes into play.

In the video, the child claims that he is the cause of his parents’ hardships. The parents’ financial situation and their struggles to earn enough to put a child through school is not the failure of the state but this child’s disability. The video does not question the high costs of school fees, the lack of financial and social support and the case-by-case basis in which one receives this support. In truth, there are not many school options for children with disabilities, barely enough childcare centres and caregivers’ support.

The parents seem to be carrying all these challnges on their own, as they comfort one another. There is no portrayal of extended support systems outside of this family, made up of family members, friends, organisations and community because in reality there is little or none at all. Living with disability is alienating. The mother desires for the child to be independent. So that he is able to take care of himself when they are no longer alive. The burden of the child’s future is placed solely on his ability to be independent. What happens to him if he doesn’t achieve this in his lifetime? Do we know? Do we care to know?

The child watches this exchange helplessly as the monologue continues. This is an example of normative projections. We assume this is what he is feeling. We expect him to feel this way, that he is a burden to his parents. That his disability makes it hard for them and for him. Makes it impossible to even be in school. He goes into a seizure and recovers from it almost immediately. We assume that these feelings of normative pressures, aggravates him and the only way to eliminate these feelings, these burdens, is to eliminate the challenges that his disability is causing. To eliminate his disability.

The dream sequence begins. In my dream we are perfect. To be perfect is to be normative. Sempurna. In this dream, it is assumed he wishes to be able to play and run to his parents. In this dream he is an abled-bodied boy and his parents are finally happy. The impact of this sequence is deeply profound. As a normative audience, we are made to feel that children, parents and caregivers desire for this perfection, desire to be NORMAL. Maybe they do…BUT maybe they desire for other pertinent imaginings; support outside of themselves, financial health, options and choices. Maybe they desire something more than just this fantasy of the normative.

In Curative Violence, Eunjung Kim wrote:

Curative violence constructs the normative body by inducing metamorphosis according to its own determination of benefits and harms, as established by how closely disabled bodies resemble and mimic the normative body. Attempts to cure physical, mental, and sensory disabilities and certain illnesses unveil the ways in which disability is enmeshed with gender and sexual norms that serve individual, state, and activist purposes. Curative violence adds to the efforts to expose what Judith Butler calls “normative violence”—the significance of transactions between subjects and the institutions that gain power through their ability to normalize certain bodies. Butler recalls, “I also came to understand something of the violence of the foreclosed life, the one that does not get named as ‘living,’ the one whose incarceration implies a suspension of life, or a sustained death sentence.” In this transaction, the major goals of the sovereign nation-state are to secure superior ethnicity, heteronormativity, capital growth, and gender conformity. Rather than being commensurate parallels, sexuality, race/ethnicity, and gender intersect as means of curing disability by making it possible to approximate the normative body, even when such approximation cannot be achieved in all respects.

And then we come to the ending. The child is seen sitting up from the wheelchair, smiling widely and walking towards his parents. An approximation of the normative body. The POV is broken and we finally see the child only when he is performing this normative approximation. This is honestly a narrative that has been going around in a lot of media representation. Some divine miracle happens and a physically immobile person is sudden able to walk, or take a few steps. This is accompanied by rousing music (preferably on strings) that builds up with each step. BIG CRINGE OK. THIS HAS GOTTA STOP. Being independent is not mobility in a normative manner, it is not walking on your two-legs like most of us do. It is not being able to talk for non-speaking folks or suddenly having sight and hearing magically returning to you. Disability is not something that can be cured in a normative way. Miracles are a fetishisation of hope in hopelessness. NOPE OK, NOPE.

Divinity as an intervention is greatly conditioned in most of us Malay-Muslim individuals. If you pray hard enough, God can cure you or your child or your family member of their disability (more on that later).

Ableism is a multi-headed beast with many words that carry nothing but hurt

I received diagnosis of a brain anomaly in my unborn child when I was five months pregnant. The first experience of ableism is when my gynaecologist insisted several times for me to terminate the pregnancy. I checked, to be sure, and asked about the health of my child and whether it was possible to monitor this during the pregnancy. She advised termination as the best option. My partner and I sought out other gynaecologists and specialists who provided useful advise and ways to monitor the baby’s health throughout the pregnancy. After thinking things through, we decided to continue with the pregnancy.

Ableism is many things:

It is frustration of not being able to apply for insurance without an extra rider fee. “You should have applied for insurance when your baby was four months old in gestation” says the insurance agent matter-of-fact as though this is something all new parents knew. “Now with this condition, you have to pay extra.” A whole lot of extra, in the hundreds.

It is shocked when an extended family member on your partner’s side visits on the second day after birth to inform you that no one in their lineage is born with disabilities.

It is hopefulness when being told “she looks fine, there is nothing wrong with her” or “don’t worry she will outgrow the seizures” or “start praying, God will make her better”.

It is hopelessness when your child still goes into seizures no matter how hard you pray.

It is rejection from friends with children who stop inviting you for playdates, after that first or second time.

It is the gaze of a stranger, longer than a gaze, a gaze that is a stare which is followed by questions you have no answer to but is expected to answer.

It is sitting with a friend after hours hearing them share about their love interest who is unable to read (“I have no future with him”) or their neurodivergent sister in law who is staying with them (“She is hard to live with but I have to take her in because no one else would”).

It is the remedies they offer, cook her soup made from goat’s feet, place her barefoot on grass before the sun comes up, durian or something stranger, I don’t even want to remember them.

It is the loneliness, nights where there is no sleep but you cannot seem to find anyone to share your exhaustion or to listen.

It is being told, Oh our company is unable to take care of children who needs administration of medication.

It is in the classroom when the therapists stops working with your child because they do not know how to anymore.

It is being told, “It’s a pity you cannot go back into the workforce because you have to take care of your child.”

It is not being able to afford private intervention programmes.

It is being approached to make art with autistic children because they assume that all disabilities are autism and that since I am a parent of a disabled child, I should engage with other disabled children.

It is having no language to talk about your joy when your child finally walks without being an ableist yourself.

It is being asked by close friends or family member, but did the doctor tell you when?

It is being asked about her future. Constantly.

It is a slur being used on social media, the same slur you hear fall out of the mouth of a seven year old who couldn’t get a word out from your child at the playground before running off as his parent looks away.

It is Insyallah, she will walk and talk soon.

It is being asked what your diet was when you were pregnant by a pregnant friend so that her unborn child is not disabled.

It is being told there is a place in heavens reserved for parents of disabled children. It is being told they are children of heaven and are a test from Allah but also a gift. And I wonder which is it now?

It is not being able to enter a place because there is no access ramps.

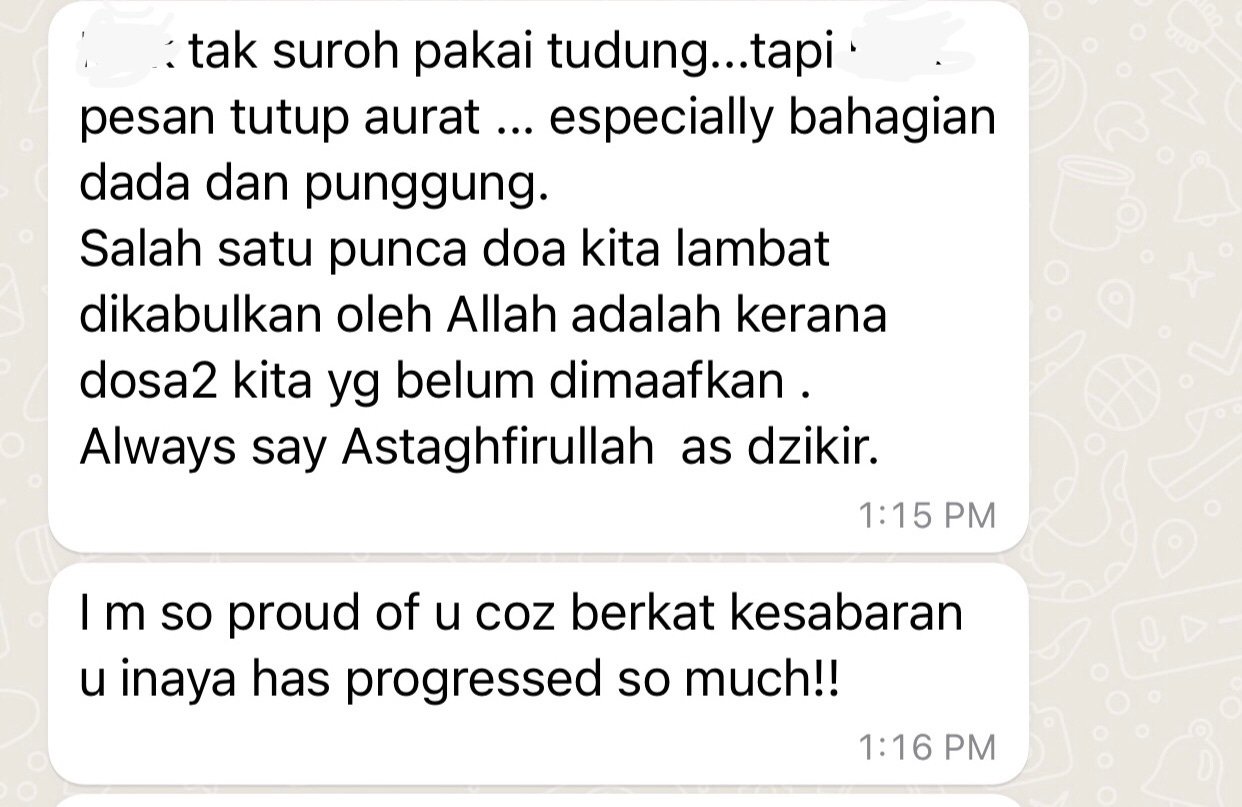

It is being shamed for not covering up because your sins slow down your prayers from coming true.

It is not being able to enter the lift which is always full of abled bodies at a mall and waiting for a good whole ten minutes trying to calm a child who cannot wait.

It is going the long way, always.

It is the sneer from the rearview mirror from the taxi driver because your child is having a meltdown

It is hearing a friend apologise to her mutuals for not informing in advanced about your child’s disability in case it made them uncomfortable.

It is being moved to apologise for taking up space, for taking up time. It is being moved to explain, my child is disabled, even though I do not owe anyone an explanation.

It is inclusivity, but not really.

It is a neighbour looking at you with sympathy and saying, “it must be hard on you” and you want to scream back and go it is hard because of people like you.

It is teachers' grabbing your child’s hands without telling her first even though they know this causes discomfort and you have informed them a million times.

It is having no options.

It is the knowledge that your child has no friends of her age.

It is the knowledge that your child has no friends except for you and your partner.

It is only being able to see your child’s disabilities and nothing else.

Ableism is not ableism immediately but it becomes a small barrier at first, quickly turning mountainous as your child grows older. It is that bleak sticky clinging that leaves a hollow in your chest, it is heavy and lonely and difficult. It is not wanting to leave home in fear of unfettered reactions, usually through actions and always through words that cut and hurt but says nothing at all.

The tunnel with many rooms does not feel like the end of the world but a start of many worlds

So here’s the thing. This cavernous tunnel has many rooms. A room that resonates with laughter, a room that hide us, makes us invisible, a room that fortifies and gives no fucks, a room that gives all the fucks that it has energy for. There is a room where there are no words needed, a room that nourishes A room that keeps us awake all night. A room that holds anger and many other rooms that opens and closes.

In the centre of it all is this almost six year old child, non-speaking floppy legged clumsy and silly, all arms and legs (how did you grow this tall child?), the one who high fives all her favourite neighbourhood friendlies, throws her voice out singing, screaming gibberish, knitted brows deep in thought, who laughs at fake crying and kicks like a horse and fake cries until she is crying for real, who hates to be touched without being asked and is a constant radiating brightness in this tunnel. And in all the rooms we’re in, she’ll wake us up in the morning with the biggest smile followed by a whine to be carried out of her cot that grows smaller each night as she bites her blankie to sleep, helps with chores by carrying pillows as big as she is, catches up with us, talks to the book shelf and the kitchen walls, requests for twinkle twinkle little star on repeat and stims by pulling and twirling her hair in her hands but hates when we try to brush out the clumps.

I find myself refraining from writing this part of it all because this is not about how my child is luar biasa or extraordinary, how she is beating the odds, how she is normative passing. No, this is not about that and yes she is so much more in my eyes but she is also just an ordinary cheeky almost six year old, who asks for selfies with the sounds she makes and only calls me mama when she wants something so badly. And I learn so damn much from her every single day I don’t even know how to write it or say it without it folding itself and morphing into some inspiration porn some of you might use to get off on. My child taught me how to listen, how to read, thought me about stimming and brought me through big heavy words, (such as proprioception, corpus collasum, grief, gratitude) open up worlds where the complexities and simplicities of difference exists at the same time and not as binaries opposing each other.

In Leah Lakshmi Piepzna Samarah Care Work Dreaming Disability Justice:

“Mainstream ideas of “healing” deeply believe in ableist ideas that you’re either sick or well, fixed or broken, and that nobody would want to be in a disabled or sick or mad bodymind. Unsurprisingly and unfortunately, these ableist ideas often carry over into healing spaces that call themselves “alternative” or “liberatory.” The healing may be acupuncture and herbs, not pills and surgery, but assumptions in both places abound that disabled and sick folks are sad people longing to be “normal,” that cure is always the goal, and that disabled people are objects who have no knowledge of our bodies. And deep in both the medical-industrial complex and “alternative” forms of healing that have not confronted their ableism is the idea that disabled people can’t be healers.

Most sick and disabled people I know approach healing wanting specific things—less pain, less anxiety, more flexibility—but not usually to become able-bodied.”

I’ve learnt too, over the last five almost six years from all these daily horrific encounters that I can always decide what, from the dreary and cruel outside, goes into this cavernous tunnel, although some of them do seeped in from time to time, insidiously and without me knowing and the hurt never really goes away.

I’ve learnt the kinds of encounter I want to seal inside: when a driver asks to take our time coming in without being patronising and laughing at my child’s antics without asking yucky questions, when an educator friend echoes the challenges I face at my child’s school without hijacking the narrative and instead affirms them and recognises it’s shitty, when my child’s babysitter talks to my child and acknowledges what she likes in a natural conversational way, when a parent friend explains to their children what disability is and do not expect me to do that labour.

So please normies, do the damn work, satiate your own curiosity, do not project your normativity unto others and always read the room. Simple gestures goes a long way. Be kind, be better.