....it came from nowhere

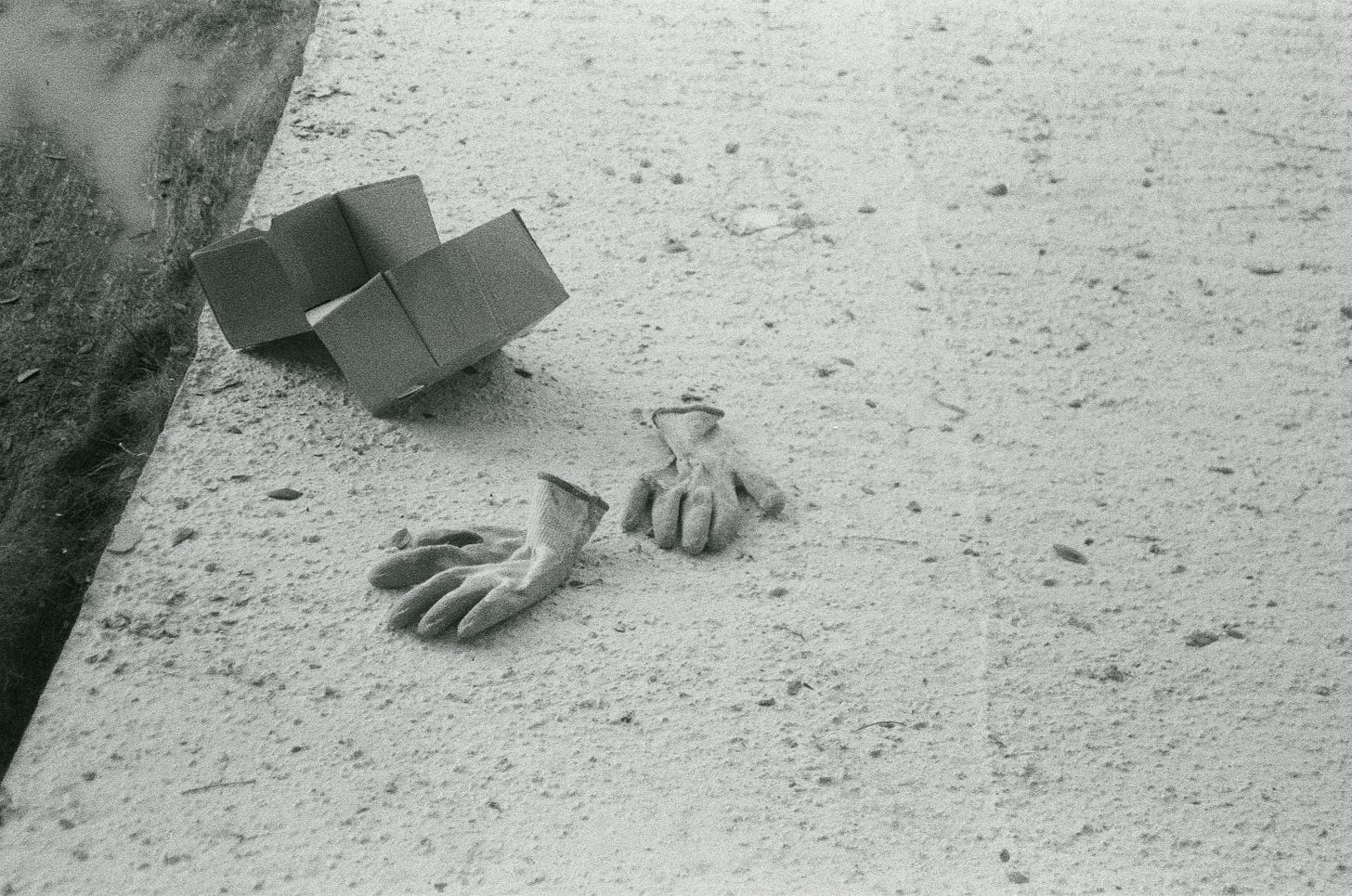

The water source is a little dry this season, splatter and drip on warm concrete as I trawl through this tenacious muddying after a lukewarm half diagnosis.

CW/TW: Substance abuse and horrors of the health care system. (The second trigger warning is more triggering than the first, tbh)

(i) “No matter how deeply I go into myself…”

Are you sure you are not on anything right now? He had asked a second time, eyes squinting into a sneer, with a mocking emphasis on the words sure and you just in case I missed it the first time. Of course I am sure, I replied sounding annoyed but when the words left my mouth it came out as a tiny weak and watered down “yeah”. I looked around the room, this clinical square space with an obtuse desk right in the middle. Empty walls with an empty hearted man. He had come in half an hour later than the appointment time. He did not apologise for being late. Instead his mouth open up as though he was towering over me, the words coming out of them merciless and cruel, sharp and bullet fast.

He looked at his monitor screen, faced away from me as though my possible afflictions must be kept secret from myself. Before this he had asked for my history of drug use, one I had given in this very same room to some other kinder doctor two years ago who had readied a tissue box and held me with his eyes. When I looked into the eyes of this doctor, all I felt is some repulsion, some inconvenience. Oh you don’t have it? I asked and he ignored me. When was your first time and what did you take? I counted backwards…Seventeen, sixteen, first time is what exactly, a long bus ride, a double decker bus to a house with no rooms. A friend housed me for a day as I missed my curfew coming home. You can stay over but my sister and her husband is a little bit…mmm wild, he had warned.

We arrived pretty late. There were only four of us in that living room, sofa bed by the wall, big floor space. I was fifteen, not sixteen or seventeen. Too young for this my friend warned when his sister offered me some, a small pack of shiny yellow pills. What’s that I asked. Power, he said, that’s what it’s called as he chugged down about ten at one go. Romilar, makes you move like a horse, it’s wild. You ok? I was and then I wasn’t. I watched as the three bodies came apart, soft liquid bodies, bursting in loud and disintegrating. Their eyes were glass, no…mirrors that reflect my own darkness. In between all the incoherence, my friend told me I should get some sleep at least. But something pique in me that night, kept me awake. Not really a curiosity, something deeper, a desire of sorts that seem to come from a dark thing that’s always been inside me….

Maybe it was seventeen then…bodies bend over the green barricades, all four of us, hands clasps tight, readying for a yawn and squealing with delight. Liquid horses. I had stayed with M in Bukit Batok for weeks after leaving my father’s house. Kau nak try tak, sM had asked and it was the same thing from that strange night. I was no longer too young for the real thing. But ni main-main punya, M said. Not the real thing but it’s ok. We get you the good stuff soon enough. And that was that, my body marked for life by the desire, this dark pleasure, first liquid, then electric before it became powdered glass that put me to sleep or crystal smoke that kept me awake for weeks. Was it addiction, then only as observer or was it only after the real thing? Was it addiction when I wanted nothing else other than*…I tried to peek into the monitor and mouthed almost a whisper, I cannot remember…

When was the last time then he asked, disarming me back into this room, this clinical room, his clinical face, I wanted to hit it with the back of my hand just to watch it turn, become real, become slightly human. The questions came fast and hard one after the other, how much did you take the last time, what did you take, when exactly? Maybe all this is because of that, he said. What exactly is that, I wanted to ask. But he did not allow for any space for me to interject. Were his questions meant to lobotomise me? Throw me off my guard, break me down even though I was already breaking. With his eyes still fixed on the screen, he started listing down all the symptoms, asking me if I was able to get out of bed…I have to get out of bed, I’m a parent of a disabled child who requires around the clock care…I cannot afford to not…Then it is not that serious, he interjected

What if this was serious, if I, the person in this room was already falling apart, already unable to discern reality outside with reality inside, what then? Isn’t this a kind of failing before the help even came through to their doors, before being placed gently in their hands, before…Isn’t this unnecessary madness for someone who was already drenched in it? So are you sure you are not on anything right now? He asked for the third fucking time. Is it ok if we do a tox screen? I went inside myself, a cocoon of bright anger made from holding in a scream. This is ridiculous. I do not wish for anyone else to be going through this but I knew that these encounters are frequent enough that lists of reliable doctors, queer-friendly, trauma-informed, sensitive practitioners have been going around the margins. I felt sick from that knowledge. Do you feel elated all the time he asked. No I feel sick. Sick? How so? I feel like I want to hurt you right now but I only managed a shrug of the shoulders and a silence made from a wall that he had laid for me brick by brick, with each question, with his repulsion, with…This person tasked to make that sick feeling go away managed almost effortlessly to make me fall deeper into this sickness…

***

It takes a while to break a wall once it is built especially if it’s not built by your hands. As I spend the last few weeks months, some days hacking aggressively at the wall and other days gently chiselling at the its weak spots, the wall have come out in parts here and there. My mind filled with its choking debris. The horrors of that morning ended with a four week dosage of an anti-psychotic, Risperidone and a half diagnosis of Bipolar 2. What’s a half diagnosis you ask? He wasn’t really sure but he still had to do his job before the hour was up. I had to stabilise my moods first, with the help of the meds and come in for a second session. In a toilet stall while trying to catch a midway stream of pee into a plastic bottle, I had cried silently and laughed a little at this whole ordeal. Here’s your fucking tox screen you fucker and I hope you get a few months of diarrhoea. Yet the morning did not really end just yet.

I naturally looked up the etymology of diagnosis aside from the diagnosis itself. Diagnosis comes from Ancient Greek διάγνωσις (diágnōsis), from diagignṓskō, “to discern or distinguish or literal meaning, to know apart (from another) or thoroughly, from διά diá, between + γιγνώσκω (gignṓskōien) to learn, to come to know. To know apart from…From what, post and pre diagnosis maybe, is it to discern the self from the madness, the condition from its symptoms? I don’t know but it is safe to say that the thoroughness of any diagnosis is as elusive as the condition itself. The process of discernment involves the labour of narrating dysfunctions vividly that are then matched (clumsily) to symptoms, confirmed through prescription of medication that might or might not work. On top of that, this thoroughness is only achievable if by some luck, said patient do not suffer from adverse side effects that closely resemble existing symptoms. Mmm, make this make sense?

On the other end of this diagnosis spectrum is the thoroughness in which the learning unfolds. I think of the διά diá in the word, between knowing and not knowing fully, between that before space of hands stretched out grasping in the dark with the after space where pockets of light are streaming in creating lines of connection that was not there before. Of course my diagnosis is still not confirmed yet but the symptoms are all there, have always been there it seems but from when exactly? Where the hell did it come from?

It is also in this between space of figuring where and how and when and what now, as I scour through post after post on Reddit or beam brightly at the thought of myself as a neurospicy gworl or exchanging information with folks who have been shuffling through a cocktail of meds and the horrors of the health care system. It is in this between space of knowledge that I am finding the most comfort, with this maybe diagnosis unfurling inside me, as I go deep inside myself.

Reading up on bipolar, I learnt a couple of scientific factoids in how it affects the brain as I try to understand if I picked it up, or was afflicted by it and when, when did all this happen, where my brain had began to glitch, the grey matter thinning around the prefrontal cortex, the shrinking parts of the hippocampus, wonky neurotransmitters with too much of this and too little of that. Was it my history of substance abuse that had damaged all these parts or was bipolar the cause of it?

Maybe a diagnosis is just that, a movable thing with many parts, or in this case many openings leading me to the other deeper parts of myself I never knew existed. All those sleepless nights since I was a child, my hyper productive periods, the slippage and then sinking into the dark. And then some kind of baseline. Which parts were truly me and which parts came from the condition? Or are all these parts too entangled to be discerned, set apart from each other? Does it matter, does it truly help to know, or rather get to know all of it, even in its shifting and changing? In the last few years as I sought to find stable ground, deep within myself, an uncontrollable force floods in and drowns me and yet I feel somehow I am finally learning to swim.

**

(ii) “The Woods of Illness are Wordless”

As we wait for the hours to pass before our gig, I recounted to A my horrible experience at my psych session. I tend to do this, recounting of my traumas. A habit I picked up to soften the pain of it, that paralysing feeling. Here I accompany my pain, with someone else who may be accompanying theirs and we fumble through it together. Sometimes it helps to laugh at the absurdity with someone who understands but undeniably it is to quell the loneliness that can cause more harm than the sickness itself. A listened deeply as we manoeuvre ourselves through the abysmal and oppressive structures of the health care system. Immediately after they forwarded me a link to an article. You have to read this, they said excitedly.

In Neither Chaos Nor Quest: Toward a Nonnarrative Medicine, Brian Teare recounts his own experience with chronic pain and his struggles in getting proper diagnosis, treatment and support. But it is not THAT kind of story. Taking off from Arthur W. Frank’s The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics (1995), a foundational text for narrative medicine broken down into three common types to describe the narratives of illness: restitution, chaos, and quest. Restitution is the classic narrative arc, the popular one we all consume with victorious cheer and good feelings in which “the healthy person becomes sick and then they become healthy again, a quick, clean plot that reifies health in ways too naïve to be meaningful”. Chaos narratives however is when “the unlucky ill suffer without plot, their nonnarratives untouched by restitution or even just movement toward suffering in a more agentive way” Then there is Frank’s favourite which is the quest narrative where the “ill person finds the strength and agency to turn their experience of illness into allegory, a journey of insight gained from suffering…feature a “communicative body” that models for others that patients can ‘accept illness and seek to use it.’…’Becoming seriously ill is a call for stories….’”

I read it several times, not for anything but how it comes close to what I’ve been struggling to express for a fucking long time. Since I was a child, hospitals and clinics have been kind of a mainstay. One of my earliest memories was running down the halls chasing after the automated mechanism fixed to the ceilings as it sends patient files from room to room, my mother running closely behind me. I developed chronic asthma before I turned one, and my parents spend countless nights rushing me to the hospital so that I can catch my breath. I was praised for being able to down medication in syrup form half asleep without as much of a gag and heading right back to sleep.

If it was not hospitals, it would be clinics. A sick child is an expensive child and my mother still begrudged me for it. Her having to quit her job to nurse me back to health. She reminds me this all the time. Many years later I relive the same cycles with my own daughter, these time consuming clinic sessions with several therapists. I’d tell my mother that I am exhausted and frustrated at the futility of it all. They don’t understand. They don’t know what else to do to help us. They tell us it’s a wait and see situation. They don’t know how to read her. My mother would snapped and say, now you know how it was like taking care of you. Here the loneliness moves its arms around my mouth and hold the words in.

Teare challenges first the quest narrative as this oppressive framing of illness having some form of, according to Frank, “higher purpose, and that redemptive meaning not only can but should be fashioned out of pain” and then wonderfully dismantles the chaos narrative altogether by recognising that yes, although it is in a language that is harder to hear because “the anxiety these stories provoke inhibits hearing” the biggest problem with Frank’s narrative medicine is that it “underplays the fact that it’s the medical–industrial complex and its caregiving archons who allow patients to speak and who decide whether to listen. Nothing ensures that they actually can listen, or will understand what they hear. Though narrative medicine encourages patient speech, trusting as it does that even the pain of serious illness can be transformed into language, when it listens it insists on hearing only a certain kind of narrative—even after acknowledging that the requisite authorial distance is often impossible for a patient with a “chaotic body” whose only story “is a non-self story.”

This is what we have learnt from the healthcare system, this is what it had taught us. Or those of us who are not afflicted by sickness. That being sick is our problem and that it is our responsibility to rise up against it. That illness is something we fight hard to extinguish with sheer determination and if we start recognising the fallacies of this kind of thinking we are rendered weak and easily defeated. That it is ours and no one elses’. And only when we have ascended that we will truly be redeemed. Inadvertently, we have stopped to listen to each other, to look out for one another.

I experience this several times ever since my child was diagnosed with a rare brain anomaly four and half months in utero. My partner and I struggle at every point. Each time she falls sick, our world falls apart because we find ourselves in the densest parts of the wordless woods of illness. The number of times we’ve been given a wrong diagnosis, or told to “wait and see if it goes away on its own” had been antagonising and deeply isolating. For a fucking long time, I thought we were the problem. That maybe this is the consequence of not being able to afford private health care or not being able to communicate with enough clearly enough to access the necessary treatment.

Within the same essay, Teare then referenced another study, The Body in Pain by Elaine Scarry, and although this is specific to physical pain, I truly feel it is also applicable to situations that are similar to ours, in which the narrative is not normative:

‘“Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it, bringing an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language.” Because physical pain rends language, renders it in tatters, Scarry argues, “the success of the physician’s work will often depend on the acuity with which he or she can hear the fragmentary language of pain, coax it into clarity, and interpret it.” Scarry acknowledges the patient whose pain makes them incapable of narrative: what language such a patient might offer is necessarily fragmentary. In the situation Scarry imagines, it’s not the patient who, through miraculous ingenuity and fortitude, transfigures their pain into story. Rather, it is the doctor or caregiver, who listens with acuity to what language the patient’s able to offer and interprets it with nuance and care…”

Fortunately though, akin to learning this new language together, we as caregivers have developed our own way around these shortcomings, learn how to get ourselves out of the densest parts of the wordless woods into some kind of clearing, not just through narratives but learning to listen deeply to these failures and finding other ways to amplify what is discernible, our daughter’s change in appetite, the way she smells, how deeply she sleeps, setting boundaries of safe touches and not-to-do’s for practitioners, giving them a detailed history before we come in for our appointments, cutting wait time, having a series of questions already ready on hand. This is how we advocate, push the clinical nature of the health care system into the parts of the woods where the sun streams in, where we learn to see beyond just the words but instead listen out for the paths towards…as Teare puts it “a careful reading of the text of pain”… or in this instance of the text of non-normative nonnarrative conditions; illness, sickness and disabilities.

(iii)”my God is dark, and like a webbing made / of a hundred roots that drink in silence.”

It’s been three months almost on Risperdone. The drug itself is slowly losing its efficacy but the side effects have somewhat remain. There are fifteen possible side effects and I strike them off the list every few weeks. In this moment, I have noticed my metabolic rate has significantly slowed down. My mouth feels like the Sahara dessert. My bladder has morphed into a deathstill sucking all the water from my body and emptying it out into the bowl at least 8 times a day. I replenish myself with all types of fluid but still feel like a thirsty house plant. My lucid dreams are creeping back into my sleep and my sleeplessness are getting more frequent.

On Reddit someone calls Risperidone the mother drug that would whack the mania into obedience, keep it under control. Someone else talks about how gaining 30 kg in three years is an ok trade for at least having some kind of normality, someone else talks about man boobs that lactate and how it’s a permanent side effect. I cupped my boobs in my hand when I read this but they seem to still be about the same size. Someone else talks about another drug Abilify as being worse than Risperidone and some other person disagrees. I stay up to read these posts sometimes until my vision becomes blurry, which is also a known side effect.

My moods remain in check though. My thoughts have their volume down low although it still moves at hyperspeed, only this time in whispers. Unlike Lexapro, which gave me really vivid flashbacks and made me feel as though I was high on expired Mollys, Risperidone feels like nothing. I bite half of the tablet off each night, roll it around my mouth, a habit I picked up from my substance use to taste the chemistry of a drug and Risperidone tastes like talcum powder, chalky and a little bit fragrant. It does not triggers my addiction behaviours like Lexapro but it does not make me feel that good either.

Sometimes, I imagine myself going off meds and maybe I might already be cured from it. But what does that mean truly? I had always been like this. This mania, or in my case, hypomania, has always been there. I remember weeks of sleeplessness as a child. Often times, I would pretend to be asleep, but remained awake in bed just letting my thoughts drift until the wee hours of morning. As I grew older, I’d had spend those nights reading, or accompanying my mother, who was also afflicted with insomnia. She’d be organising the storeroom or ironing the clothes. When my father came home, I’d rushed in bed as though I had been asleep and my mother kept this from him, our little secret.

There were also periods of heavy depression. I was plague by it my entire life. Strangely I could always feel it coming before it hits and only recently I’ve learnt that as the body chemistry starts to glitch, the body experiences tactile signals. On December 2017 I tried to write about these signals:

before it hits, I would feel it in my fingernails, antennas carrying whispers in waves, cryptic in form. sometimes these whispers were for the world, sometimes it was for me. I could never tell. if I bring my fingers up to my ears, I could almost hear it, soft electric lines, mischievous and teasing, like a warning when I hit a slope but I am already slipping and I could feel myself falling. I would bite my fingernails in futile efforts to stop it but these waves would move frantically from one finger to the next, catching infectious sighs in between them. slowly these waves would move up into my fingers and swirl in my palms, warm air dancing in circles higher and higher and suddenly I am birthing hurricanes. I clenched my palms against something hard, someone else’s hand, proximity of conversations, objects as distraction. i’ve never been told how soft desperation becomes against the rigidity of control, turning into fluid screams that is drowning inside me. it moves, undulating, unforgiving right into my belly, fractals of blue, manic yet empty and I become stone, a heavy concrete slab of feelings, feelings that has no names for them.

Origin late Middle English: from Latin depressio(n- ), from deprimere ‘press down’ (see depress).

to press down. maybe depression describes more so the attempts at stopping it rather than what it really is; open flesh wounds submerged in seawater, a shard of glass, too small to be removed wedged in between my fingernail, a thin wire wrapped around my neck tight enough to make me grasp for air but not lose my breath, eyelids sewn slightly together, so they remain open yet I am unable to shut them tight. that is only the tip of it, the rest of it remains trapped in a visceral layer of wordlessness. nothing is pressed down; its a mad dance on a burning floor. there is no downward in this spiral but a haphazard recoil of agony breaking in all directions. sometimes it hits someone I love and they feel the pain so I hide. sometimes it bounces off the walls and all I can do is to keep hiding until it find its way back inside. nothing…can be pressed down.

and I wait until it passes, like everything else.

Now, although I am much aware of what it is, I am still wondering where it comes from. I wonder too about how even with increased doses and stronger meds, the depression always return and, as though having absorbed all these temporary defences, has acquired new tricks and grown formidable. Why does it keep coming back? In an article Is everything you think you know about depression wrong? by Johann Hari published in 2018, of excerpts from his book Lost Connections: Uncovering The Real Causes of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions was also asking the same question and writes:

‘Why was I still depressed when I was doing everything I had been told to do? I had identified the low serotonin in my brain, and I was boosting my serotonin levels – yet I still felt awful. But there was a deeper mystery still. Why were so many other people across the western world feeling like me? Around one in five US adults are taking at least one drug for a psychiatric problem. In Britain, antidepressant prescriptions have doubled in a decade, to the point where now one in 11 of us drug ourselves to deal with these feelings. What has been causing depression and its twin, anxiety, to spiral in this way? I began to ask myself: could it really be that in our separate heads, all of us had brain chemistries that were spontaneously malfunctioning at the same time?’

In his search, Hari found that this brain glitching chemistry imbalance is not the sole consequence of our collective malfunction. It is the lives we live and our environments that play a large part of it as well. He writes:

“So, what is really going on? When I interviewed social scientists all over the world – from São Paulo to Sydney, from Los Angeles to London – I started to see an unexpected picture emerge. We all know that every human being has basic physical needs: for food, for water, for shelter, for clean air. It turns out that, in the same way, all humans have certain basic psychological needs…. And there is growing evidence that our culture isn’t meeting those psychological needs for many – perhaps most – people. I kept learning that, in very different ways, we have become disconnected from things we really need, and this deep disconnection is driving this epidemic of depression and anxiety all around us.”

He referenced an official statement release for World Health Day in 2017, the United Nations concluded that “the dominant biomedical narrative of depression” is based on “biased and selective use of research outcomes” that “must be abandoned”. We need to move from “focusing on ‘chemical imbalances’”, they said, to focusing more on “power imbalances”. And therein lies the rub, when the system has ingrained this dependency solely on internal change, with the health care system at the centre of it all, treating the internal symptoms of pain instead of transforming these power imbalances of the external environments in which it came from.

Hari likened this deep disconnection and its dysfunction as a form of grief. “….This pain you are feeling is not a pathology. It’s not crazy. It is a signal that your natural psychological needs are not being met. It is a form of grief – for yourself, and for the culture you live in going so wrong. I know how much it hurts. I know how deeply it cuts you. But you need to listen to this signal. We all need to listen to the people around us sending out this signal. It is telling you what is going wrong….”

So what then ila, what now? Well, get to know my grief I guess. Give it a warm bright hug and welcome it in. Accompany the fucking pain all the way through. And not by my fucking lonesome. In an interview I’ve found in my sprawling search, and one which I read a thousand time since, Francis Weller a psychotherapist who specialises in grief and sorrow through rituals of renewal, describes society’s aversion to grief creates “a depression that is more of an oppression”. He writes:

But now we’re asked — and sometimes forced — to carry grief as a solitary burden. And the psyche knows we are not capable of handling grief in isolation. So it holds back from going into that territory until the conditions are right — which they rarely are. The message is “Get over it. Get back to work.” Again and again in my practice clients come to me with a depression that is more of an oppression: a result of so many years of sorrow that have not been touched with kindness or compassion or community. You’re left with an untenable situation: to try to walk alone with this sack of grief on your back without knowing where to take it.

Weller then describes a flat-line culture from our compulsive avoidance of difficult matters and an obsession with distraction. He describes this too as an ascension culture. “We are an ascension culture. We love rising, and we fear going down. Consequently we find ways to deny the reality of this rich but difficult territory, and we are thinned psychically. We live in what I call a “flat-line culture,” where the band is narrow in terms of what we let ourselves fully feel. We may cry at a wedding or when we watch a movie, but the full-throated expression of emotion is off-limits”. We are that society that schedules a crying session facilitated by tearjerking films or songs or whatever sad thing that comes along but when its some real shit that open the floodgates we do it in secret or mediated through a screen.

And the best part that got me was this. That somehow has kept me open amidst the body horror, mind fog, emotional flat lining, the trial meds and half diagnosis, amidst the social isolation and my inability to cry. So I am just going to copy the entire chunk of it and end it here for now. Thank you for reading this large clunky thing. May we find ourselves accompanying the pain, move beyond the wordlessness and listen deeply to our signals.

Till next time my loves. Hydrate, ressociate and stay in love.

**

McKee: How can we make ourselves more receptive to that downward journey?

Weller: The bias against going down arises from our cultural conditioning. Christian mythology teaches that resurrection and ascension are the proper directions for a spiritual life. The very earth is seen as a fallen place, and our bodies are perceived as fallen objects that can be redeemed only by the soul finally getting out of this tawdry place and moving on to its final reward. You rise above, getting better, higher, and lighter. But low-lying places of regression, of descent, of lamentation are not less sacred. Poet Rainer Maria Rilke writes, “No matter how deeply I go into myself / my God is dark, and like a webbing made / of a hundred roots that drink in silence.”

Right now your heart is beating in utter darkness inside your chest. You were conceived in the dark of your mother’s womb. Everything that is happening aboveground is because of what’s happening below, in the shadows. We have to descend into the dark, yet we are continually trying to climb out of it. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell Blake said we have to go to heaven for form and to hell for energy, and marry the two. There is vitality in that move. I notice a kind of anemia in a certain sort of New Age spirituality. There’s not much blood in it. It lacks the black earth of what in Spanish is called duende: the erotic, juicy energy that makes things shimmer. Blake knew that much of that energy is cut off from our lives and relegated to hell. So we have to go into the shadows and bring it back out. Our hyperpositive tendencies want us to do a spiritual bypass around the mess of it all, but it’s there in that mess that we are most human.

Ascent and descent should vitalize each other: when you polarize them, you end up splitting off what is “good” from what is “bad.” We praise success and despise failure. We value strength and devalue weakness. But then every time we encounter defeat, inadequacy, or loss, we’re at war with ourselves, and that’s a bitter fight. A client apologized to me the other day for “going backward” in his work with me, as if forward were the only acceptable direction. But the psyche moves every which way. It’s our job to follow its lead and be curious about where it is taking us.

Think about how much energy we expend trying to deny and avoid these parts of ourselves. What if all that energy were available to us again? We would laugh more. We’d know more joy. Life is asking us to meet it on its terms, not ours. We try to control every minute detail, but life is too rambunctious, too wild. We simply can’t avoid the losses, wounds, and failures that come into our lives. What we can do is bring compassion to what arrives at our door and meet it with kindness and affection. We can become a good host.

thanks for writing this. I felt it deeply