"rouse the sly nerve up, that knits to each original its coarse copy"

I (try to) unpack the multiple selves, before (and beyond) the metaverse: This begins with a bodiless bust in some tree and loops into itself some fluid time continuum of transmissions and legacies.

1. the grisly visage endured

Many moons ago I stumbled into rivers, myths and mourning, all contained in a book written by Olivia Laing titled To the River. After a bad breakup, she decided to mapped her heartbreak on a sojourn through the Ouse, where Virginia Woolf had drowned herself in 1941 by filling her pockets with stone. Olivia’s narratives fluidly moves through personal experiences, historical facts and her fascination with Woolf’s life and writings.

When passing beneath a bridge and encountering a graffiti on a wall of a woman’s face looking out with empty eyes, Laing’s wrote how the face struck an echo with her as she recounts this:

Both Plath and Hughes wrote poems about the bust that haunted them both in different ways. This disembodied, bodiless, bad copy of Plath that was tucked into a trunk of a willow tree, out of sight but somehow that cord, where Plath had wrote, knitted to its original, stubbornly remained intact and continued, “refusing to diminish”

Here’s the full poem,( I am not adding Hughes’s poem simply because it’s Hughes but you can look it up yourself):

Fired in sanguine clay, the model head

Fit nowhere: brickdust-complected, eye under a dense lid,

On the long bookshelf it stood

Stolidly propping thick volumes of prose: spite-set

Ape of her look. Best rid

Hearthstone at once of the outrageous head;

Still, she felt loath to junk it.

No place, it seemed, for the effigy to fare

Free from all molesting. Rough boys,

Spying a pate to spare

Glowering sullen and pompous from an ash-heap,

Might well seize this prize,

Maltreat the hostage head in shocking wise,

And waken the sly nerve up

That knits to each original its coarse copy. A dark tarn

She thought of then, thick-silted, with weeds obscured,

To serve her exacting turn:

But out of the watery aspic, laureled by fins,

The simulacrum leered,

Lewdly beckoning, and her courage wavered:

She blenched, as one who drowns,

And resolved more ceremoniously to lodge

The mimic head—in a crotched willow, green-

Vaulted by foliage:

Let bell-tongued birds descant in blackest feather

On the rendering, grain by grain,

Of that uncouth shape to simple sod again

Through drear and dulcet weather.

Yet, shrined on her shelf, the grisly visage endured,

Despite her wrung hands, her tears, her praying: Vanish!

Steadfast and evil-starred,

It ogled through rock-fault, wind-flaw and fisted wave—

An antique hag-head, too tough for knife to finish,

Refusing to diminish

By one jot its basilisk-look of love.

—————

Mimicry of the most frightful nature comes from the likeness of a face. One experiences a tingling of discomfort when glimpsing for the first time, a pair of identical twins separate from themselves. An uncanny feeling as though the duplication or in some cases multiplication are glitches waiting to re-merge or be removed.

I think about that urge to capture likeness, to possess it, a copy that last for eternity, in the different mediums over the years. This too, seems to be closely tied to how technology has been shaping our lived realities; from painting to photography and of late copious amounts of social media logs as though we are trying to achieve immortality, no longer a coarse copy but one that is seamless and immaculate. One that is closely knitted to the original.

There is, as most may know, a morbid end to this story, the bodiless head an unforgiving foreshadowing of Plath’s own death. Plath somehow knew maybe, as Hughes wrote in his version, titled The Earthenware Head, the lady missing from the title:

Surely

Your deathless head, fired in a furnace,

Face to face at last, kisses the Father.

But the ill copies reign strong, the grisly visage endured these years long after her death. Looking for the poem, I did a quick search for Sylvia Plath and the terracotta bust and was amused (and slightly disturbed) by the results. Several heads of the dead poet propped up on a white pedestal inscribed with Sylvia Plath (1932-1963). The expression it carries is the most confounding, half-smiled eyes looking up as if scheming and thinking loudly “I made it after you”, as if formidable. I wonder how Plath would feel to know her heads are up for sale.

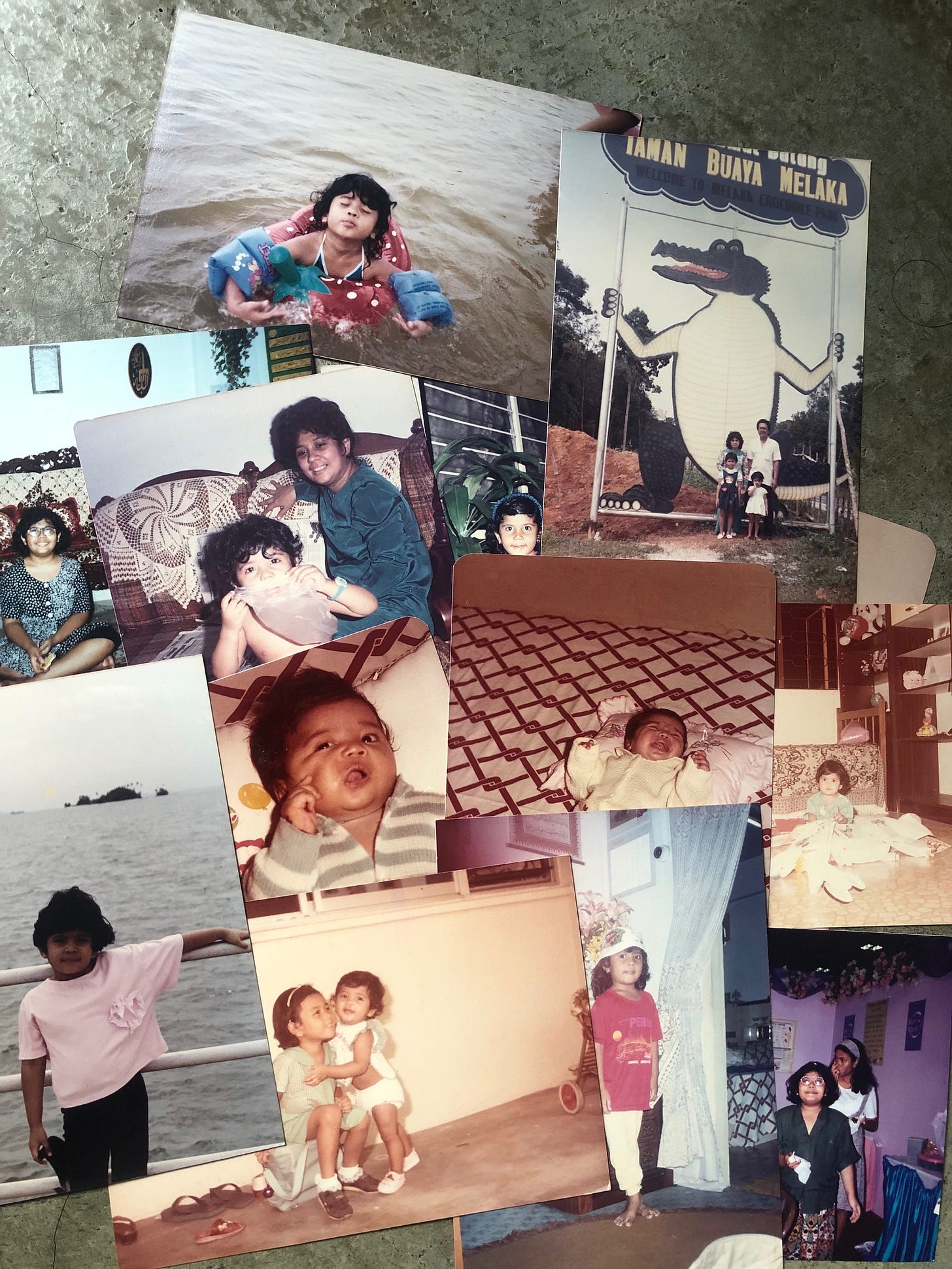

2. “When do I see a photograph, when a reflection?”

I think about these copies across my own life, tracing it to the very first; my photos as a newborn that I went looking for in a dusty shoebox; red-faced, mouth wide open, an animated still that seemed so alive. As if in some other verse, I am caught in a mid-cry forever. I find myself in different ages, forced occupants of this crowded shoebox-cave. A chaotic, non-chronological repertoire of nostalgic candidness. Memory slices printed on photo paper of different sizes (mostly 3R) and taken by different family members over the years, mostly my mother but some by my deceased grandfather. In this box too I find photographers older than I: my favourites are the one of my mother as a girl (maybe ten) with high socks and another one slightly older and a photograph small enough to fit into a wallet. My face a copy of hers and her face a copy of my own child.

There are some photographs I keep returning to, again and again. Replaying these memory in my mind, as vivid as a photographs would allow, replicating the same expressions, the same landscapes, the same moments. Effigies of memory, knitted to the original that guards them from forgetfulness. Because of technological accessibility though, our own relationships with these type of family photographs have changed over the years. I have about 20,000 images and videos, 3/4 of them are of my child, stored since 2016, the year that she was conceived. They remained unprinted and much like the shoebox, have not much use until maybe, an offering made from a feature found on Google photos that pick out the best ones and put it in an album with sappy titles such as Over the Years, edited with the same sappy style complete with some stock soundtrack that is meant to tug at the heartstrings.

Digital copies such as these seem to be an unnecessary accumulation of data, more alive and abundant than the flatness of photographs but lacking material connection. This format moves away from the coarse copy and closer to accurate representations of the original. Maybe that’s why there is a carelessness, as though the elevated copy will be more formidable in its own protection against forgetting. I store these archives on my 2TB iCloud that is financed at $12/month because it is easier to ensure that nothing is lost than to go through all these images and decide which ones of them are worth keeping. Everything is important in keeping with the aliveness of it all, one memory stitched into the next, even if these copies are banal repetitions of the same moment. Uh the reverse may hit the hardest if one loses data storage or if the data becomes corrupt or inaccessible and everything disappears.

Much like my mother and grandfather, I continued on making pictures of my loved ones with film. I have printed some of these copies, placing it on the magnetic door of our storeroom, a careless shrine of sorts. Passing them several times a day, ubiquitously as though one would a kitchen sink or the sofa. But somehow these copies too seem to trigger the same replays, though less overtly and almost unnoticeable, softer and diluted versions. I am less reckless in my keeping of these physical copies, copies of myself with my child, copies of myself in my child , although without any urgency to hold on to these moments as tightly because they are not too far gone. I wonder then maybe after my passing, where will these printed photographs end up? In a different shoebox maybe inherited by my child much like how I’ve inherited mine? Or in the hands of a stranger, kept alive for other reasons beyond mere reflections of a time or space, mere reflections of myself.

3.The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feelings

In one part of Ted Chiang’s The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feelings, an older journalist unpacks his concerns through his research on a new technology, Remem that is designed to allow people to access and shift through their lifelogs using keywords and function as an assistive tool of memory. Lifelogs are essentially tools that record every single moment in one’s life as a video diary of sorts. With Remem, people are able to recollect with accuracy moments in which are remembered wrongly or not remembered at all, say the last place you put your keys or for heavier surveillance purposes promising transparency of one’s actions as everything is recorded.

One concern that was raised was how forgetfulness is necessary in moving on, the “psychological feedback loop” is impossible if every moment is fixed indelibly into a video and there is no softening, no room to experiencing these moments differently, no space for hindsight or retrospect. The journalist mentioned the differences between semantic memory, knowledge of general facts and episodic memory, recollection of personal experiences:

“We have been using technological supplements for semantic memory ever since the invention of writing. First books then search engines. By contrast, we historically resisted such aids when it comes to episodic memories…We regarded our episodic memories as such an integral part of our identities that we are reluctant to externalise them, to relegate them to books on a shelf or files on a computer. That may be about to change… For years, parents have been recording their children every moment so even if children weren’t wearing their personal cams, their lifelogs were effectively already being compiled…

Imagine what would happen if children begin using Remem to access those lifelogs… Their mode of cognition would diverge from ours because the act of recall will be different. Rather than thinking of an event from their past and seeing it with their mind’s eye, a child will subvocalise a reference to it and watch a video footage with their physical eyes. Episodic memory will become entirely technologically mediated. The obvious drawback for such a reliance is that people might become virtual amensiacs whenever the software crashes. But just as worrying to me as the prospect of technological failure was that of technological success, how will a person change the conception of themselves when they’ve only seen their past through an unblinking eye of a video camera.”

He went on with:

Regarding the role of truth in autobiography, the critic Roy Pascal wrote, “On the one side are the truths of fact, on the other the truth of the writer’s feeling, and where the two coincide cannot be decided by any outside authority in advance…It seemed to me that continuous video of my entire childhood would be full of facts but devoid of feeling, simply because cameras couldn’t capture the emotional dimension of events…Part of me wanted to stop this, to protect children’s ability to see the beginning of their lives filtered through gauze, to keep those origin stories from being replaced by cold, desaturated video. But maybe they will feel just as warmly about their lossless digital memories as I do of my imperfect, organic memories.

There is definitely a monolithic quality to externalised memories, in this case the copy: captured and manufactured into data that is codified so that it lasts, and that it becomes THE only accurate representations of the original. This is what happened. This is how I remember it. This is how I remember myself. The copy is dead, long live the copy.

4. Sympathetic Magic and the puaka of likeness and legacies

All that aside, I cannot ignore the magic of a copy, a kind of puaka or what Laing wrote as sympathetic magic. We’ve all heard of (and watch it in so many films) of black magic violence made potent if placed upon the photograph of the victim. Nowadays it seems easier to buat orang. Just do a simple search on Google of the person’s full name (this too is necessary in casting a spell on someone) and digital copies of this person splayed out in a line on the screen, convenient and vulnerable to be possessed.

Out of curiousity of my own digital visibility, I did a quick search on Google of my name, firstly just ila, which brought up acronym for different companies and organisations. I added in Singapore into my search and voila, I found different copies of myself, relating mostly to my art practice and past exhibitions. (Also I am bottles of premium whiskey.) In my performances, especially when it’s in the video format, I have consciously kept my face covered, intentionally as an act of erasing my personhood from the work. But in recent years, and in some works, my face (and body) is visible and hyper present.

Unlike Plath’s bust though, all these mimics are intentionally made, a reclamation to how I wish to be perceived (or not perceived) by others, strangers mostly across the virtual realms. On the other end of the spectrum is then the representation of the banal, on all my social media accounts. Strangers may catch copies of myself (and others in my physical space) in all manner of likeness, laughing, dancing, cooking, keeping up with viral trends before they grow stale, DAILY. Hyperreal copies of myself that another user or a social media peer, may think that we are well connected, besties, up to date, even though we have never met in real life. It’s almost an urge to consistently provide this updated copy to keep it alive and in tandem with time.

I had a conversation with a friend who refuses to have any digital visibility or presence. It’s safer that way, she confessed. There is no data trace and people will be unable to cast an evil eye, she added as if these are two different tangential safeguards she is taking. I quietly felt that these are the same things, having fallen under that spell-cast of internet dependency; the gratification of being witnessed, the power of creating my own immaculate copy, in exchange for a different kind of puaka. There’s so many fragments of me floating about, “no place it seems for the effigy to fare, free from all molesting”.

Going back to the puaka, imagine then that a little bit of one’s essence is trapped within all kinds of representation, a photograph, a latex mask, a video on a loop. Is that why I feel so emptied out each time I finish making a work and set it out for viewing? Or after a live-modelling session where different representations of me are birthed on paper and continue to live on someone’s else’s folder? Is this the same as the unease Plath felt even after the bust is no longer within her peripheral vision but still “refusing to diminish”? Maybe not. Maybe it is something more sinister. A copy, no matter how intentional it is in its making is still a copy that can be, consumed, exploited maybe, accessed, manipulated, I don’t even know actually.

5. Glitch: “On the rendering, grain by grain.

I think of communities way back when, that resisted having their voices recorded or their photographs taken. Entrapment of souls, ghosts in machines. This year I made a work in which I replicated my face (and that of my collaborator) using latex. The likeness is uncanny, especially when I hold these latex face masks in my hands. There is a strange disembodiment that I experience, not at all to looking at my own reflection in the mirror but a kind of rapture or slippage, a kind of glitch. Probably that is closer to the unease Plath felt. I still get little goosebumps though, when I peek inside the tote bag in which I keep these masks and catch them peeking out.

But then, I think of Remember Me, a wonderful and intimate project by the artist Divya Koswaji about her grandmothers and there is an allure to this notion, a kind of legacy, of remembrance.

What happens when a person dies? Do all their thoughts and feelings die along with them? What of the things they leave behind? Do they count if there is no one around to love those things? What if you are that person? What if nothing is nothing and everything is full of invisible meaning? What if everything they left behind were all yours to cherish, and therefore all your burden to bear?

I remember standing mesmerised and staring at the loop video of her Dadima dancing in a black and white film uttering the words: “Right here is the time to be alive,”. An enchantment, a time portal, a magnetic spell cast and I was transported. Maybe Dadima is still dancing, still singing “Everyone has to die so let’s live a little first”. I too want to be caught in a video, an image, many years from now in multiple permutations and manifestations. Fragments of myself dancing, moving in water, naked against a tree, smiling widely. Fragments of myself activated, screaming wildly singing these damn words. “Where will a time like this come back again?” Maybe these fragments are emptied out of me into other forms and into other worlds, and fill up into the bodies of others, rousing the sly nerve up. The copy need not always be grisly, need not be accurate, nor remain singular and controlling, controlled.

In Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism on Glitch Encrypts touches on these fragments and multiplicities as simultaneous occupation of some-where and no-where, no-thing and every-thing.

“We consent not to be a single being frozen in binary code, and as such, consent, not to be a single site. This embrace of multiplicities is strategic as glitch bodies travel outward through every space, we affirm and celebrate failure to arrive at any place (YAAAS). Far beyond fixity, we find ourselves in outer space exploring the breadth of cosmic corporeality.

And so let’s keep glitching these copies, celebrate them, press hard on delete and let them remain in slippery places within ourselves and others among us. May these copies birth copies and copies of worlds, rousing sly nerves, rendering grain by grain, in every space and may they remain unreadable through all of it.