(i) citizens of longing

“In Greek, the word eremos can be applied to a lonely person but it also means a desolate place. There’s a doubleness to this lens, a reciprocity: when people monopolize a place we often deprive ourselves of sharing it with other living beings”

—The Age of Loneliness: Essays by Laura Marris

Sungai Api Api, 4:45pm

I retraced my steps trying to navigate through the boardwalk maze, slightly dizzy by the pierce of sunlight through the stilt roots of the elevated Rhizophora and the thrill of cicadas. Without looking at the time, I knew that evening is close to the horizon. I had been looking for the birdwatching tower but always seemed to be arriving to another sheltered dead-end, a place to sit or read another informative plaque wrinkled and faded by humidity about the kinds of flora and fauna one may be able to spot in these parts.

It always take some time to find bearings, to adjust to the lesser-felt rhythm of an unruly place, though here at Sungai Api Api, the unruliness is held together by manmade order, shaped to be accessible enough as the wild is kept at safe distance. I stood and stared for a while at the different species, trying to discern which ones were obtained from Malaysian estuaries and reintroduced to existing species of Avicennia (or the namesake of the place, api-api species) to support regeneration in the area and which ones had been there from the start of it all. I could not tell the difference of course.

In the last months I have gotten slightly better at distinguishing the different species by looking at the roots, their flowers and fruits; have moved through so many mangrove forests both on land and through water, have yearned for the brackish air and the enveloped stillness during the pauses in between these visits, have tilted my body closer each time peering longer trying to attune myself to their animacies. I came across a plaque at the start of one of the boardwalk entrance of fireflies conservation at the park. Visitors are encouraged to visit at night to encounter them but yet somehow as blue hour approaches, I was slightly skeptical. Not so much of the existence of these fireflies but of its waning appeal to the wider public.

I grew up in a mangrove forest that had been stripped bare to make way for an industrial town, the first of its making. Famously described by economist daddy and mastermind Goh Keng Swee as “building a great city from a mangrove swamp1”, the mega reclamation of Jurong was his leap of faith. Our family moved there the year I was born in 1985 and I spent most of my childhood in that sleepy neighbourhood prone to frequent blackouts that lasts for hours at a time. We’d come out with our torchlights, held it beneath our chins and chased each other until the lights came back on or we’d go to the playground to catch some fireflies.

I remember the dim flutter of fireflies and swinging an empty container to catch several at a time and watch the light glow. I remember it clearly. In the small world of my neighbourhood, this was one of my earliest memories. However mangroves were long gone by then and fireflies going rogue and travelling (from where?) all the way to our concrete patch of blocks and emptied field seemed ridiculous but there they were and there they are still pulsating in my memory. Have they returned to the ghost of this place, in search of mangroves to feed and mate only to find our faces and our hands trapping them inside plastic? There is a quality of loneliness to this memory, my failure to place them to their exact time and place or to their natural habitat from long ago, to make them come alive again.

In the book of essays titled Age of Loneliness, Laura Marris recounts loneliness as a reminder: “Biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer puts it like this: ‘As our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated, more lonely.” I started to wonder if, in the Eromocene, loneliness could be a helpful feeling because it makes it harder to overlook what’s missing. There’s a strength — a stubbornness—to being lonely, to insisting on the importance of what’s no longer there. To wonder why you never hear a certain bird anymore…To realize while passing a beach, that there used to be many more horseshoe crabs. Unlike grief, which is acute and often a response to finality, loneliness hums in the background, but if you tune in to its frequency, it can reveal something about the ways people have often become more isolated from the living world. Loneliness is worth listening to because it longs for reconnection—a hurt that illuminates its antidote, a system that desires its cure.”

Finally I reached the bird-tower and made my climb. Upon reaching to the top, I saw three kingfishers air-wrestle each other before flying off behind me. I take in the many sounds of birds and cicadas, of the rustling stream, of traffic not that far away. I locked away all I’ve encountered for the day; vinegar crabs slow crawling out of their mounds, the bright green elongated fishes in the river swimming round the sunlight. And in those moments I try to capture the unseen, the ten rivers that used to flow into Sungai Api Api, now buried or transformed into canals, the mangroves that surround their perimeters, the luxuriant green. What an impossible act to remember something that is long gone, and oh how lonely it feels to do so.

Maybe all of us are citizens of longing, for reconnection to a more expansive world beyond the human though most of us may have forgotten how to tune in to their frequencies. I breath in the air trying to make a place with all of it and place them in my memory in case in time to come, these too would disappear.

(ii) how things hold

How has the question of ‘how things hold’ come to such importance? This question grows out of the turn to the concept of ‘assemblage’. In earlier social theory in both ecology and anthropology, ‘communities’ were the focus of social cohesion. Worried that this concept overemphasized a taken-for-granted social solidarity, scholars in both fields have turned to assemblage, a more loosely imagined grouping. But this opens the question of how entities in an assemblage relate to each other. With growing evidence of symbiosis and interdependence from ecologists and evolutionary biologists (Gilbert and Epel 2015; Margulis 1981), theorists have reimagined the assemblage not as a static set of autonomous elements but as a dynamic process of ‘becoming with’ (Haraway 2008). The image of the knot has emerged as a way to imagine cohesion without a prior assumption of collective solidarity. Donna Haraway (2003: 6) has described the world as “a knot in motion.2” Deborah Bird Rose (2012: 136) writes of “embodied knots of multispecies time.” Tim Ingold (2015) imagines knots as nodes in meshworks of lifelines. The word ‘knots’ offers a vivid image of interconnection within the assemblage. How do knots work? This article suggests that knots form through attunements in which humans and non humans can align with each other through timing to make living in common possible. In this way, concepts of assemblage and of coordination require each other. Juxtapositions of beings gain force as assemblages when relations of coordination are thick within them.

—HOW THINGS HOLD A Diagram of Coordination in a Satoyama Forest by Elaine Gan and Anna Tsing

Semakau, 10:45AM

I steady myself on the boat, one hand holding a DJI camera trying to capture the different offshore islands we were passing along the way. F had lit a cigarette and maneuvered the boat expertly with one hand. I’ve counted the number of times I’ve passed by the area in the last three years. Maybe three, maybe four? F started naming all the islands and these names have become familiar. What remains is that sense of unease as I pass by Bukom and Jurong islands, the hard and shiny metal structures against the lapping waves feel as though these manufactured landscapes is on the brink of collision and collapse.

F is a Semakau descendant and spend the brightest days of his childhood on the island. Most of the offshore islands he had named, with the exception of Pulau Hantu, are out of bounds and have restricted access. And yes that includes Semakau. Semakau was amalgamated to another island, Pulau Sakeng and transformed into the first (and only) offshore landfill. When one does a search of Semakau, what always comes up is the bio-efforts to ensure that pollutants from the trash do not contaminate the sea and its engineering feat to service the entire island’s trash. The inhabitants of both islands, who were relocated in the early nineties are always, only briefly mentioned.

As we neared Semakau, F pointed to some columns sticking out at the shore. That’s where my great-grandmother’s house used to be. Behind the shore, the mangroves are dense and lush. I asked F if these mangroves are the replanting efforts that were made and he told me that those are grown on the perimeter bund instead of the land itself. The reintroduced mangroves in the reclaimed areas were planted to be the first line of defense in case of contamination3. Did the land reject these efforts, refuse to accept the state’s terraforming attempts?4

On our way around Semakau, we spotted many things, a fish that skittered across the sea to avoid our incoming boat, a stingray that only F saw, several birds we could not named. Here we are on sea, assemblages in coordination with each other. Here we are becoming with each other, the sea and the sky, and the dense mangrove forest, the faint smell of trash that was similar to dried squid, bird calls and the low hum from the refineries. I find myself attuning to each slightest motion, restlessly looking around as though landlessness requires something deeper to ground myself.

As we turn into the edge and neared the mouth of the river, F recounted how he’d walk the whole island with his two dogs at his side, pausing for a bit before exclaiming it was freedom! I wonder how F feels to only be able to circumnavigate the outskirts of his home but never allowed to walk the land like he used to as a child. F told me that there are two rivers in Semakau, here where we were, is Sungai Penyalai and the one nearer to the landfill is known as Sungai Ah Meng, named after a man who used to stay there. The tide was too low for us to enter the river. A bird is chirping right above us but remain unseen.

With nothing left to do, F suggested that all f three of us try line fishing. He anchored the boat down after standing and looking for a spot. From his chiller box he took out a small bag of prawns and fix a line. He hook a piece of prawn and threw out the line and in less than five minutes, he caught a fish. I want to try, I said holding out my hand. He threw out the line and handed it to me. Feel it land on the seabed and then give it a tug. I followed his instructions the best that I can and seconds later my line was dancing. I pull it out and there at the end was a Spanish Flag gasping for air with a hook in its cheek. I was petrified but also intrigue.

F told us that he is able to identify the fish just by feeling how the line moves. He also tells us how when he’d bring his son and wife to the spots with the most fishes, his son would ask him how he knows. When he say he knows because he lived here, his son did not believe him. What else can he say, he knows because he knows. This just how things hold I thought. By the end of the hour all of us had our own line and was trying our luck. F told us that when the fish is too small, it goes back to the sea. When asked what we do with the prawn heads, he told us that too goes into the sea as a kind of barter trade. We give and take; we take something and return something back.

Before we returned back to mainland, F brought us to the landfill. We passed by the new area that is being reclaimed littered with bulldozers and cranes. F told us we must keep a 2 meter distance as this is a highly restricted area. Then he brought us to the Cyrene reef but the tide was not low enough. He says its beautiful here and we could walk around during low tide. He pointed to the reef saying it’s really big but it only looked like the sea to me. On our way to the compound we talked briefly about the Long Island Plan in turning parts of East Coast into a freshwater park by building a wall as a defense against rising tide. Imagining how this is eventually disappearing a part of a sea permanently, I felt nauseated.

Momentarily that morning we were a knot in motion. Coordinated. With the tide being too low, we ended learning how to fish. The stories F told flow in and out the most during that time and I could feel them, heart aching and deep longing for all that he has lost. Assemblages of bodies, beyond space and time, I was allowed to encounter what still persists even in the absences. That his loss was my own and ours to bear, and that was how things hold. Juxtapositions of beings gain force as assemblages when relations of coordination are thick within them… and we are thick within the grief and the love that remains.

(iii) datok sungai penyalai and the mother mangrove

“The biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer has written about what she calls the ‘grammar of animacy’—the ability to recognize in language, the life forces of the earth and other species, ‘the word-less being of others in which we are never alone.’ She writes that in Potowami, the language of her ancestors, many things that she had known in English as nouns were actually verbs. “To be a hill, to be a sandy beach, to a be a Saturday are all possible verbs in a world where everything comes alive,” she continues. “Water, land and even a day, the language a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world, the life that pulses through all the things, through pines and nuthatches and mushrooms.” On the other hand, “A bay is a noun only if the water is dead.”

For those of us who are used to thinking in English, our language is wildly disadvantaged in this area… Many elements of the nonhuman world are referred to not just as nouns but as objects. Sure a pair of scissors is an ‘it’ but so is a network of mycelium, homing through the soil in ways we’re only beginning to understand….When you’re lonely it’s hard to see yourself in the language of others. ‘The arrogance of English,’ Kimmerer write, ‘is that the only way to be animate to be worthy of respect and moral concern, is to be human.’ As a result, exploitation can fester in the linguistic distance we make between ourselves and other species. For Kimmerer, ‘Saying “it” makes a living land into “natural resources.”’… The humility of knowing that we as we live, other species are pursuing their own lives through the world of their perceptions —a vast cacophony of senses. A grammar of animacy where each verb is a different mode of existing.”

—The Age of Loneliness: Essays by Laura Marris

Seletar Island, 9:15am

I squeezed the mango until the flesh feels almost spongey before biting the top off. I sucked the juice out and was pleasantly surprised but how it had the same quality as an expensive ice blended smoothie. One of the guides taught me this trick. It’s refreshing right? he asked and I nodded enthusiastically, mouth too full of mango juice.

Huey, our main guide brought us through the labyrinth of three different areas of Khatib Bongsu in our kayaks. I have never seen mangroves this tall. In the first clearing, the mangroves canopied above our heads and the sky snaked in the space between them mirroring the river. The sun was bright and the river flowed rapidly that we keep bumping into the mangroves. My friend J patiently navigated the kayak for us as I documented all I could on video.

Again that pocket of sound, almost as though we were in a vacuumed space, was something I’ve noticed in all my site visits. Goosebumps raised at the back of my neck and arms and disappear again. Sure there are the occasional bird call and the sound of water, but at the forefront was this sound that was close to silence. Maybe it’s the frequency of mangroves, the way the water holds here in its roots, the density of air. We were mostly quiet too J and I especially when we were passing the third quarter of our trip in the mixed mangroves forest.

Mangroves have repopulated the areas of abandoned fish farms and what’s special about this particular place is that the mangroves do not cluster based on species. Instead all the different species are spread out with no kind of natural order about them. Here the pocket was the loudest and maybe that’s the reason J and I were making as little sound as possible without being conscious about it. Was this a kind of attunement? Maybe it was. Maybe it was the aliveness of it, half-submerged mangroves breathing in the water beneath us.

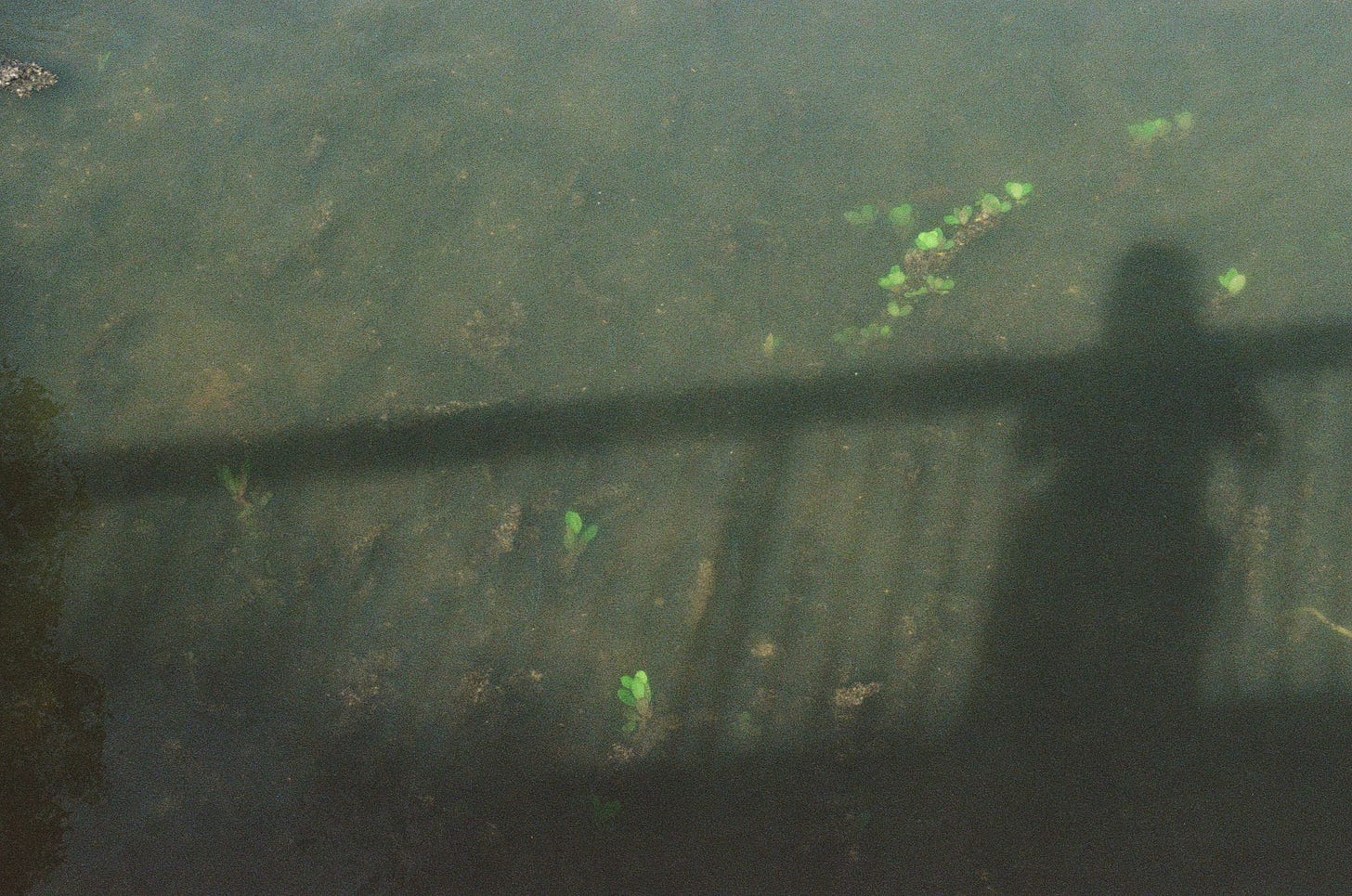

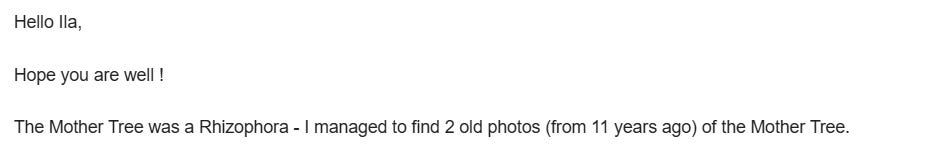

On Seletar Island, Huey mentioned how there used to be a mother mangrove about five meters tall in one of the areas of Khatib Bongsu about eleven years ago. A frequent visitor, Huey has been kayaking for more than two decades shared with us that on a return visit, the mother mangrove was no longer there. I asked if she had died and he replied that she was just no longer there. When we asked why he called her the mother tree, he told us he believed that she was the tree that birthed the other Rhizophora mangroves around Khatib Bongsu. When asked why he thought that she was no longer there, he did not give a straight answer and mentioned that it could be the pollution, or the tide levels or the changes around the area.

I asked Huey if he considered himself to be an expert on mangroves and he laughed and kayaked away before saying that he definitely was not one. I do believe though that his frequent visits over the years have increased his sensitivities to how the landscapes are continuously changing. This too is a form of coordination. I imagine that Huey, simply through this frequency of attending to these places, and paying attention to these synchronies and indeterminacies through his encounters5 have made him able to see himself in the language of other nonhuman lives.

Pulau Semakau, 12:35pm

In the same month, I was back again at sea with F and my friend X. It was raining relentlessly. As we walked to the compound before leaving the mainland, F told me that we might need to reschedule if the rain does not stop. I casually said that maybe I have not been given permission to enter sungai Penyalai. He laughed and then leaned in to tell of a guardian of the river. A two-meter high bearded figure wearing a white robe can be seen by those that he reveals himself to. He’s a good guardian right? I asked as we both instinctually rub the goosebumps that have appeared on our arms at the mention of his existence. How do you know that? I can feel it the other day, I told F. Yeah he is, he replied.

F told me that once the elderly uncles and himself went into Sungai Penyalai to catch crabs. However when they were arrived he said that the river was empty, kosong. I did not ask what he meant by that but I assumed that all the creatures were gone, no fishes or crabs, no birds. One of the uncles caught sight of the figure from his periphery, the datok of the sungai, and asked him for permission to crab there. Upon turning back around, the river’s creatures had returned. Instead of continuing on, they decided to turn back out of respect of his reverent presence.

When the rain was a little lighter, we set out taking the same route that we did a few weeks back. The air was icy cold and the waves rocked the boat. I sat behind F and held on to the back of his seat to steady myself. Finally we arrived and entered, the green of the mangroves matching the sea, as the soft rain pattered down on us. Again that sound envelop us. F told me that the river use to cut through deeper into Semakau but the mangroves thrived undisturbed upon the river and there was no way we could pass through. F kept a lookout for coast guards that may spot us trespassing and we stayed not more than ten minutes before we headed out again.

We went fishing for a bit and this time around I managed to catch seven parrotfish or ikan tokak on my own with guidance from F. You’re getting the hang of it, he told me. It was already close to three and one of the uncles dropped F a voice note reminding him not to stay at the river at 4pm. He let me listen to the message and then smiled knowingly at me. We headed back to shore soon after.

As we were leaving the sungai, F told me of attempts to combine the island with the reclaimed parts and how these attempts have failed for the most strangest reasons. One of the working ships had sank and when it was recovered, they could not find a hole and machinery that were tasked to reclaimed the space between the two masses had broken down several times. My favourite was the story about how the sandpipes measuring a few meters long, held down with bolts and nuts on the sea bed to release sand, had disappeared overnight.

I’ve thought a lot about these two encounters in the last few weeks. These old beings, the mother and datok and all the other reverent spirits that inhabit these spaces. The way the land and our nonhuman inhabitants are always resisting and fighting back, repopulating areas that they were removed from, remained as silent and steadfast guardians, animacies of absences. I think of their language, of concealment and collisions, their frequencies and this feeling, this yearning for the knot to remain in motion, to remain coordinated to other rich nonhuman lives beyond our own. As the genocide continues on and lives and land are continuously being stolen and destroyed, I hope that the aliveness and animacies of love persists amongst us all.

Thank you reading this far my loves. Stay hydrated, ressociate and stay in love <3 Till next time.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19720228-1.2.81?qt=qualities,%20vital,%20to,%20our,%20growth&q=qualities%20vital%20to%20our%20growth

https://www.xenopraxis.net/readings/haraway_companion.pdf

“The landfill’s original design kept a narrow channel between Semakau and Sakeng, but experts determined that the channel’s hydrodynamics meant all the mangroves on the east side of Semakau would not survive the resulting tidal changes. So engineers constructed the perimeter bund, and replanted 13.6 hectares of mangroves to replace those that had been removed to build it. The replanted mangroves would serve as biological indicators of leaking waste” -https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/50/a7668b86-9a47-4cef-9b33-fc71217552fb/case-study-singapore-pulau-semakau.pdf

Doing a search online about the failures/challenges of the restoration attempts at Semakau only mentioned an oil spill and nothing more.( https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/50/a7668b86-9a47-4cef-9b33-fc71217552fb/case-study-singapore-pulau-semakau.pdf). However several individuals who are part of nature groups have mentioned them in passing.

“Satoyama is a landscape that is made over time, through multiple encoun ters and embodied temporalities. Representations of landscapes too often turn them into backgrounds for human actions. Attending to satoyama enables us to trace landscape’s structural features as multiple synchronies, accidental encounters, and indeterminacies.” https://www.academia.edu/38465417/How_Things_Hold_A_Diagram_of_Coordination_in_a_Satoyama_Forest