the measure of a soul in this city of ghosts

I have fallen into a clingy web of objects, energetic debris, dying estates and tear-stained notes hidden in the cracks of my <3. There is no closure in these sporadic sad thoughts.

(i) That Ghost Story

A few years back, while still fresh from postpartum hormones, I caught A Ghost Story on our first flight as a family of three. The film centres around the ghost of a man who died tragically (and suddenly) in front of his house, leaving behind a wife who grieves for him about a third of the film before moving away elsewhere. The man is trapped in space (and time), unable to communicate with anyone except for the occasional poltergeist-ish light flickers and broken picture frames. There is this scene in which the protagonist ghost (portrayed humorously in crumpled off-white bed sheets) stands at the window and notices another ghost (in floral bedsheets) in the house opposite his.

Floral Sheet Ghost: Hello

Protagonist Ghost: Hi

Floral Sheet Ghost: I am waiting for someone

Protagonist Ghost: Who?

Floral Sheet Ghost: I don’t remember.

My three-month old child was fast asleep throughout the film, in an attached modular cot right below the screen and my partner was beside me, restlessly trying to catch some rest. And there I was, trapped in my seat, an almost invisible ghost. I was holding back tears and wordlessly carrying all these bedsheet heavy feelings. Yet I was feeling immensely grateful that what I was have been waiting for were still in their material forms and within arm’s reach. (This film is so good and I will not spoil the rest. Go watch it if you haven’t and watch it again if you have. Maybe not on a red-eye flight when everyone is fast asleep)

Anyhoos, the lines that struck me pretty deeply to this day was the wife saying “When I was little and we used to move all the time, I’d write these notes. And I’d fold them up really small, and I would hide them.” He asked her what was written on those notes to which she replied, “They were just things I wanted to remember so that if I ever wanted to go back, there’d be a piece of me there waiting for me.”

What if there is nothing to go back to?

What if it is no longer there, the note, that wall, the house, and all that one wishes to remember?

What if all that is left is this wanting?

(ii) Of halts and houses

(I wanted to write about SERS and enbloc, the Land Acquisition Act1 and public housing as a running national scam that has exploited the land and profit off of its people but that honestly requires a dedicated post. Here’s a little preface to have a sense of what’s going on with Tanglin Halt and other dying estates. Tanglin Halt is scheduled, under the Selective En bloc Redevelopment (SERS) Scheme2 and demolition plans were slated to begin in the last quarter of 2021. SERS is a scheme that moves occupants from super old flats into fresh new ones, together with a updated lease of another 99-years.

For readers who may not be from Singapore, public housing is only leased to buyers for a period of 99-years. Although it may seem that 99 years lease is long enough to last a lifetime, the problem is that some of these estates, such as Tanglin Halt has been around longer than its occupants.

Tanglin Halt was one of the earliest satellite towns located in Queenstown, a kind of town centre model which has everything from schools to factories and markets with a public pool and library in one allocated area promising convenience and fostering close-knit communities. Tanglin Halt was built before independence, in 1963 and is located nowhere near Tanglin. The halt in its name remains although the KTM train lines intersecting near the present junction of Tanglin Halt and Tanglin Halt Close where trains would come to a halt is long gone. So here’s the tricky part. Because of the fluctuating property market, house prices at the point of purchase to the point of sale may inflate enormously.

In other words, an old couple in a dying estate, may have purchased a flat as newlyweds probably at $XXX. Many years later they are expected to sell their flat off under the SERS scheme only to be forced into a smaller sized flat (for enough profit to ensure their new house is at least liveable, i.e renovations cost) because a similar sized replacement flat would require them to do a top-up, a really BIG difference in cost. This is just one example of the many problems of this scam scheme. Also imagine if you are already 90, barely able to walk with little savings left from your retirement plan and you kinda settled in your home all these years but is suddenly told that you HAVE TO move out because these old flats (with “high development value”) need to die really soon so that other new flats can be built in it’s place.)

And so ends my preface.

The last few months I have visited Tanglin Halt several times documenting the process (and impact) of being made to move elsewhere. I did the same in Dakota a few years back and both times, I was particularly moved by the objects that were left behind.

There’s a forced echo in these spaces, a struggle

to catch the last few breaths before

the end. I think of you, deceased spirit,

who passed on in this dying estate, how you linger

in your room as your matrimonial bed is lifted to its sides,

leaning precariously against the walls of an area cordoned off,

towering over the furniture of other deceased spirits,

how they too cling to their houses as they are

razed to the ground. Empty ground,

land ready real estate for the next round.

Various discarded objects, all worn out from use

and time. You are in each of them.

Behind each corridor is a gathering, a quiet protest

with no words. There is nothing left to do here

but wait. I come upon overgrown plants,

root markings on walls,

the last fruits that a papaya plant bears

as it lay upon the ground with thirst.

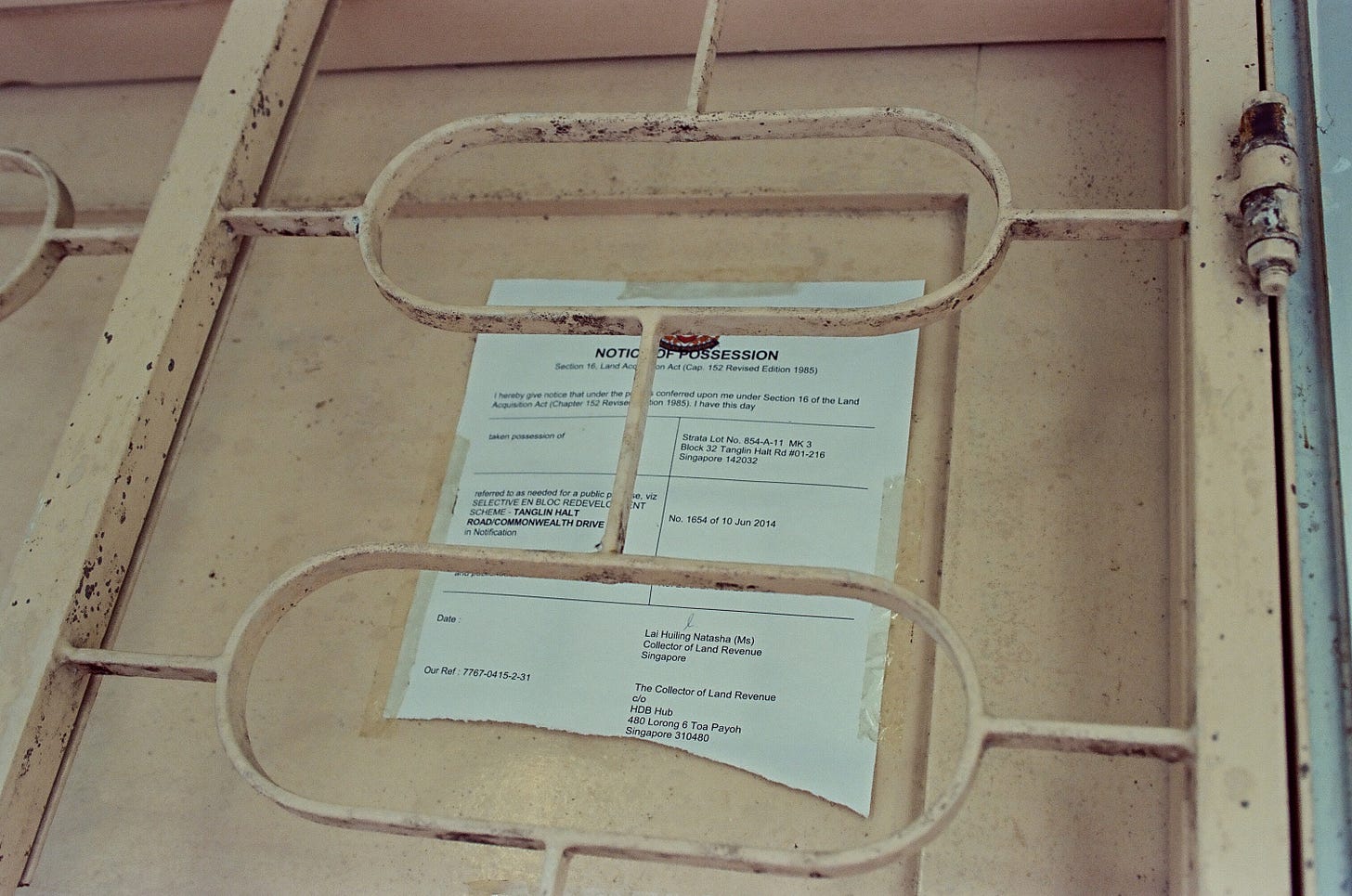

On each door is a notice, plastered cold,

a warning. It reminds me of a sealing spell

that halts the jiangshi3, stops it from moving,

a trapping talisman. On the notice it reads

“I hereby give notice that under the powers conferred upon me Under Section 16 of the Land Acquisition Act (Chapter 152 Revised Edition 1985, I have this day

taken possession of…”

Possession of…possessed. I never knew a home

can be a gamble where the odds

are always going to be against you.

At the end of each note, the name of the owner,

such a blatant intrusion of privacy. Yet

is it a crime if it has happened before? Many

times before. There is a sadness here,

banana leaves grow wildly over

that concrete seat but left

a little space empty. In case

you return, with the rest of us, to wait

a little longer.

(iii) I will never forget your cookbook full of holes

After my father took us into full custody, my mother was forced to sell our house. (Yes divorce is nasty). She moved around a lot and stayed with friends over weeks or months each time. She sold most of our furniture away and stored her belongings at a storage space for a period of three years before finally securing a rental flat for herself and my grandparents. My mother is a sentimental hoarder. She keeps everything even today; from my umbilical cord in a red satin button pouch to a container full of buttons.

Before the divorce, my mother was a working mom for a big part of her married life. Financially, both parents had to be working for us to live comfortably. She cooked whenever she can and loved doing it. At our old house where we knew our neighbours by name, my mother would cook a big pot of some delicious dish and I would carry plates of food up to Cik Ana on level 12 or down to Cik Peah on level 4. Sometimes I’ll bring it to the opposite flat, trying not to spill anything, to Cik Misah who stayed on the ground floor. My mother made the best mutton dalcha, nasi goreng, assam pedas…the list goes on and on. Our favourite was this intensively spicy fried macaroni made from dried chillies and topped with generous amount of spring onion, celery leaves, fried shallots and freshly grated cheddar cheese.

When we were younger, my mother made and sold delicious cakes to help the family financially. My first earliest memories was us sitting on our counter-top, my sister and I, our legs dangling far from the floor. She’d hand us the beater sticks from the mixer dripping with cake batter and we would lick it like it was ice-cream. Our house smelt like cookies and cakes. I remember running to the oven to stare into the hot oven door. My mother would scream and say “Nanti cake bantut” (the cake might not rise) and kicked me out of the kitchen. I fondly remember her writing in this fabric green buku hutang an accounting book). The book was probably older than I was, the green cover was already faded and the spine was coming apart slightly from use.

This book had all her recipes. The ones she created and adjusted, the ones she copied from others. It carried her generous energy and was always in some part of the kitchen. My mother cooked from memory mostly and I grew up feeling that somehow the book was a kind of guide for her to imagine ways that could help with the household finances, that gave her control over her domestic responsibilities that demanded everything out of her. It was her spell book, her magic written in words that were clumsy and uncertain (my mother left school when she was nine). Then as the years go by, as her cooking saved her and us through hard times, her handwriting grew confident and the magic fortified.

When I was much older and begin experimenting with my own cooking, I craved to flip through the pages of that cookbook. My mother and I were staying in a one room rental flat in Dover Road, with a much smaller kitchen. She cooked sometimes when she felt like she missed her own dishes or when I begged her to make some of my favourites. The cookbook was not a feature in this kitchen and the magic was long forgotten. One day I asked her about the cookbook and my mother looked at me annoyingly and said “dah takder” (it’s no more). I persisted asking her for it occasionally, picking out times where she was in a better mood. But the question would always make her mood turn and she just kept giving me vague replies or ignore me completely.

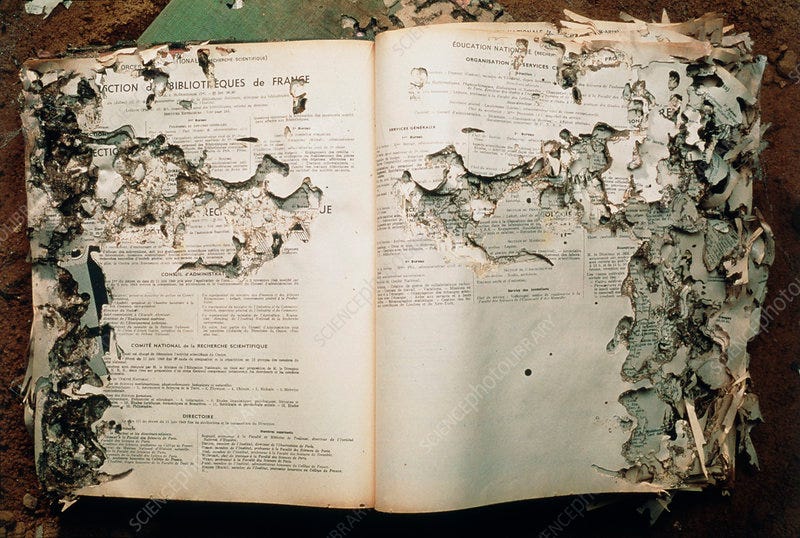

I stopped asking and gave up but one night as we were laying side by side, my mother told me about how she had kept the stuff she could not bring along with her in a storage space. She figured all her belongings would be safely kept. I can hear her voice shift slowly as she told me that a year in, she had wanted to go through her belongings. To throw some stuff away and to give some to others. To make space. She had opened one box and the first thing she took out was the green cookbook. I can hear a gentle crack in her voice. The book looked as how it was but when she opened it, the pages were full of holes. Termites have eaten through them. My mother started crying saying how broken she was, angry, and completely helpless. Everything that was stored in some of the boxes, was carelessly consumed and damaged beyond recognition.

I wanted to hold my mother that night and I wanted to tell her how sorry I was that she lost everything. I wanted to tell her that her magic is always there, more so now when it is full of holes. I wanted to tell her I will never forget that cookbook full of holes even if all the recipes are long gone. I wanted to tell her I remember all that she was and I will remember all that she is. But I didn’t. We never could communicate our affection in ways that I wanted so I lay there with her, staring up at the ceiling, holding her hard with the silence.

And then there’s this Land Acquisition Act, that makes enbloc and forced eviction legally kosher. Eminent domain as it is also known is the power of a national government to take private property for public use. Between 1959 and 1984, the government acquired a total of 43,713 acres of land and bulk of this land bank was acquired under the Land Acquisition Act after 1967. The government became the biggest landowner by 1985. Today the government owns 90% of land.

The Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme, or SERS for short, is an urban redevelopment strategy employed by the Housing and Development Board in Singapore in maintaining and upgrading public housing flats in older estates in the city-state. Launched in August 1995, it involves a small selection of specific flats in older estates which undergo demolition and redevelopment to optimise land use,

Chinese hopping vampire popularised by Chinese horror-comedy films in the 90s. The Chinese character for "jiang" (殭/僵) in "jiangshi" literally means "hard" or "stiff".